As Your Resource For Self-Development

- The Optima Bowling Coach (2025)

Cognitive–Deliberate Practice

(Page Update 2/2/26)

Inside the Optima Bowling World, Cognitive-Deliberate Practice marks the moment when human development became explicitly designable. Skill acquisition was no longer left to repetition alone, nor guided primarily by emotional attunement. Instead, learning was reframed as a feedback-rich cognitive process, in which perception, planning, execution, and correction formed a deliberately engineered loop.

This epoch reveals what human development looks like when symbolic-causal intelligence assumes a governing role, coordinating bodily action and emotional regulation through structured attention and intentional difficulty.

Historical Setting

Three major research streams converged to shape this era.

First, cognitive psychology displaced stimulus-response explanations with internal information processing models. The work of Allan Newell and Herbert Simon portrayed expertise as organized mental representations, “chunks,” stored in long-term memory and retrieved through pattern recognition rather than conscious calculation.

Second, motor learning research has demonstrated that movement quality improves through structured error detection and correction. Schema theory and closed-loop control models showed how feedback refines motor programs over time, strengthening neural pathways through calibrated repetition.

Third, social-cognitive theory emphasized self-efficacy, the belief in one’s capacity to act effectively, as a key regulator of persistence, focus, and learning efficiency.

These strands are synthesized most visibly in the work of K. Anders Ericsson and colleagues, whose studies of elite violinists articulated the principles of deliberate practice: focused activities designed specifically to improve performance, requiring full attention, immediate informative feedback, and sustained engagement at the edge of current ability.

Sports, music, chess, and, later, education and corporate training rapidly adopted this framework. Technology accelerated adoption. Video playback enabled slow-motion analysis; heart-rate monitors tracked physiological load; early digital spreadsheets logged volume and intensity. Improvement became a designed process, not a byproduct of time spent.

Coaching Expression

Four operating principles define Cognitive–Deliberate Practice coaching:

Cognitive–Deliberate Practice expressed itself through four defining coaching patterns:

- Goal Decomposition with Progressive Difficulty: Long-term performance goals were broken into discrete sub-skills, sequenced from low to high complexity. Practice environments were engineered to isolate variables and minimize noise, allowing attention to remain focused on a single developmental target at a time.

- High-Frequency, High-Quality Feedback: Immediate, specific correction replaced generalized encouragement. Video replay, timing gates, metronomes, and later sensor data reduced feedback latency. Coaches highlighted precise discrepancies between intention and execution, allowing rapid perceptual recalibration.

- Work–Rest Ratio Management: Training was periodized to balance stress and recovery. Macrocycles, mesocycles, and microcycles distribute intensity across time, protecting learning capacity while sustaining progressive overload.

- Self-Monitoring and Mental Rehearsal: Learners tracked metrics, reflected on strategy, and engaged in mental imagery. Visualization recruited visual, kinesthetic, and auditory channels, reinforcing neural pathways between physical sessions.

Together, these practices dramatically increased the efficiency and predictability of skill acquisition.

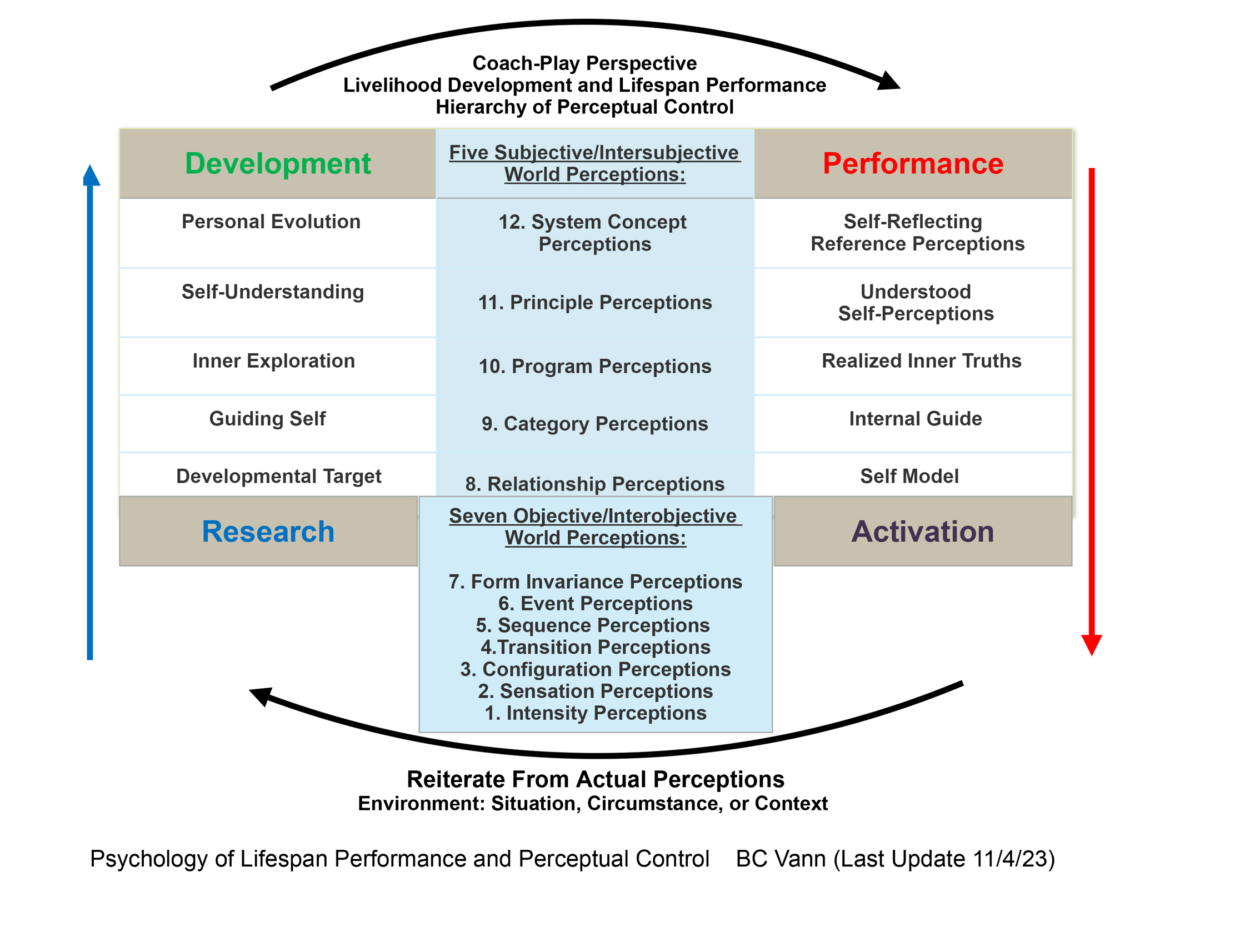

Development as Nested Perceptual Control

From a Perceptual Control Theory perspective, Cognitive–Deliberate Practice represents a refinement of error regulation. Coaches structured environments so that the discrepancy between perception and reference values remained within a narrow, productive band, large enough to trigger reorganization, small enough to avoid collapse.

LPPC analysis indicates that symbolic-causal planning governs material-sensory execution. Reference values were increasingly explicit: benchmarks, targets, performance indicators. Emotional regulation prioritized attentional stability over expressive exploration.

This refinement of error regulation produced highly controllable learning loops, but also increased dependence on explicit structure.

Plane Balance

- Symbolic-Causal Plane: Primary. Planning, modeling, and abstraction governed training design.

- Material-Sensory Plane: Strongly integrated. Technique precision and movement quality remained essential, now guided by cognitive schemas.

- Relational-Emotional Plane: Supportive but instrumental. Motivation and communication served to maintain focus rather than to pursue deeper relational inquiry.

This balance allowed rapid skill consolidation while narrowing experiential breadth.

PIE Integration Note

Within the PIE triad, Cognitive–Deliberate Practice approached equilibrium.

- Purpose was articulated as specific performance outcomes and developmental milestones.

- Integrity depended on data fidelity, accurate metrics, consistent feedback, and disciplined tracking.

- Experience consisted of repeated engagement at the edge of competence, calibrated to sustain learning without overload.

What remained underdeveloped was existential purpose: why the performance mattered beyond optimization itself.

Carry-Forward Legacy

Cognitive–Deliberate Practice remains foundational:

- Evidence-based progression underlies modern high-performance training.

- Feedback technologies continue to compress perception–correction cycles.

- Self-regulated learning practices shape academic, athletic, and professional development platforms.

Its limitations are equally visible. A narrow focus can produce tunnel vision. Excessive metric reliance can suppress adaptability. Without contextual grounding, drills risk becoming detached from meaning and lived complexity.

These tensions motivated later systemic and vertical approaches, which seek to retain rigor while restoring relational and contextual intelligence.

Reflection Prompt

Identify one skill you are currently refining. Note whether your practice emphasizes planning, repetition, or contextual application. Consider what dimension, sensory precision, emotional regulation, or systemic understanding, may now require greater attention to restore balance.

See Next: Vertical & Systemic Coaching

Back To: Humanistic Revolt