As Your Resource For Self-Development

- The Optima Bowling Coach (2025)

Humanistic Revolt

(Page Update 2/2/26)

Inside the Optima Bowling World, the Humanistic Revolt marks the historical pivot away from mechanized efficiency toward personal meaning, emotional authenticity, and self-defined purpose. It represents the moment when coaching and developmental practice attempted to correct Industrial Behaviorism’s overreliance on external measurement by re-centering the lived inner experience of the individual.

This epoch reveals what human development looks like when the relational-emotional plane is elevated to primary importance, and when growth is understood as alignment between inner state and outward action.

Historical Setting

The aftermath of World War II forced a reckoning with systems that treated human beings as interchangeable parts. Behaviorism’s explanatory power, adequate for observable performance, proved insufficient for addressing trauma, moral reconstruction, and the search for meaning. Psychology and education responded by reorienting developmental theory toward intrinsic motivation and subjective experience.

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs reframed human striving as layered fulfillment, arguing that survival and security form the base, while belonging, esteem, and self-actualization guide higher development. Carl Rogers’s client-centered therapy articulated the relational conditions—empathy, congruence, and unconditional positive regard—under which individuals naturally reorganize toward greater coherence.

These ideas spread rapidly. Universities formalized humanistic psychology programs. Esalen Institute became a focal point for encounter groups, Gestalt work, and somatic awareness practices. Jerome Bruner’s advocacy of discovery learning shifted education toward curiosity-driven exploration. Corporate environments adopted sensitivity training to improve communication and morale. Civil rights and antiwar movements amplified calls for personal voice and participatory structures.

Across domains, the developmental conversation: How efficiently can this be done? Shifted to why does this matter to the person doing it?

Coaching Expression

Four core practices characterize Humanistic coaching:

Humanistic coaching expressed itself through several characteristic practices:

- Facilitative Dialogue: Coaching sessions prioritized open-ended questioning and reflective listening. The coach adopted a non-directive stance, aiming to create psychological safety rather than prescribe action. Progress depended on the learner’s willingness to articulate experience honestly.

- Experiential Learning Cycles: Borrowing from Kurt Lewin’s action research, workshops alternated between activity and reflection. Role-plays, sensory exercises, and group dialogue surfaced emotional patterns and framed them for insight rather than correction.

- Goal Personalization: Objectives emerged from the learner’s stated values rather than institutional targets. Plans were revised as new feelings or meanings surfaced, reinforcing ownership as the primary motivational engine.

- Holistic Assessment: Narratives, journals, and group feedback replaced numeric scoring. Coaches tracked enthusiasm, engagement, and perceived self-coherence alongside observable behavior.

Together, these practices expanded the emotional bandwidth of coaching and legitimized subjective experience as a developmental signal.

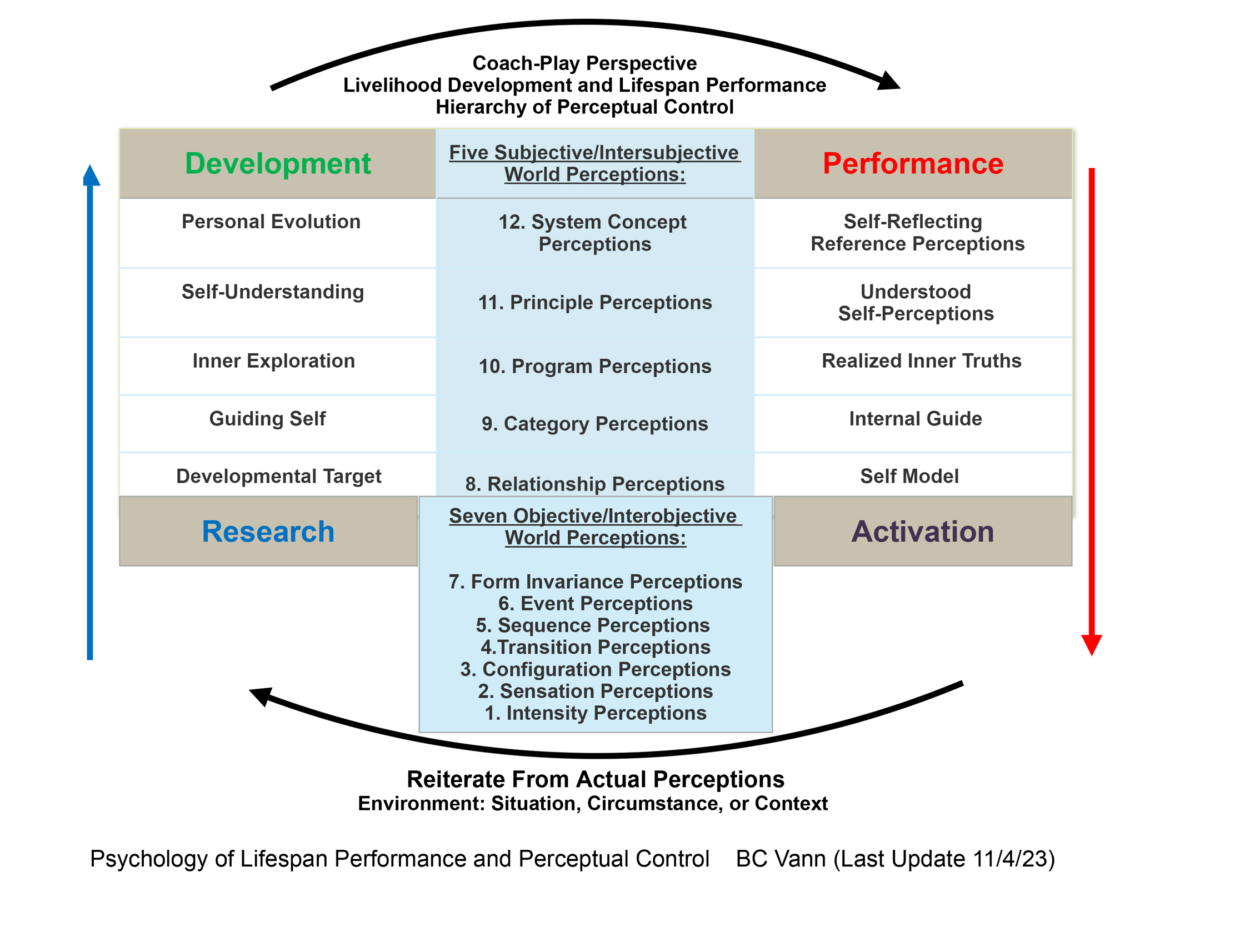

Development as Nested Perceptual Control

From a Perceptual Control Theory perspective, Humanistic coaching relocated control references inward. Rather than imposing external performance standards, coaches sought to help individuals regulate felt authenticity: aligning self-perception with expression in action.

LPPC analysis shows that the relational-emotional plane became the dominant regulator. Empathic dialogue reduced error between inner state and outward behavior. However, fewer constraints were placed on material-sensory precision, and symbolic-causal structures varied widely depending on the practitioner’s philosophical grounding.

Attempts to regulate felt authenticity produced powerful personal insight, but inconsistent skill stabilization.

Plane Balance

- Relational-Emotional Plane: Primary. Emotional congruence and psychological safety were treated as the core indicators of development.

- Material-Sensory Plane: Secondary. Technique and precision mattered insofar as they expressed authentic intent, but were not always rigorously calibrated.

- Symbolic-Causal Plane: Expanded but uneven. Purpose, identity, and values entered the developmental field, though without consistent frameworks to test their coherence over time and under pressure.

This correction addressed Industrial Behaviorism’s emotional neglect while introducing new vulnerabilities regarding rigor and transfer.

PIE Integration Note

Within the PIE triad, the Humanistic Revolt elevated Purpose to the foreground. Integrity shifted from measurement accuracy toward emotional honesty and depth of disclosure. And Experience emphasized narrative and felt sense rather than objective feedback.

The rebalancing was necessary, but incomplete. Without sufficient grounding in Experience as corrective data, Purpose risked drifting into abstraction.

Carry-Forward Legacy

The Humanistic Revolt left durable contributions:

- Empathic coaching skills such as active listening and reflective mirroring remain foundational in leadership development and counseling.

- Client-owned goals underpin individualized learning plans and athlete self-assessment tools.

- Reflective journaling continues to support the generation of insight in therapeutic and performance contexts.

Its limitations also persist. Overreliance on introspection can lead to neglect of technique calibration. Emphasis on positive affect may underplay the discipline required for high-level performance. Later cognitive and systemic approaches emerged in response, seeking to restore rigor without discarding humanistic insight.

Reflection Prompt

Recall a recent coaching or teaching interaction. Assess the balance between emotional clarity, technical feedback, and long-term purpose. Where one dimension dominates, consider a small adjustment that restores equilibrium rather than amplifying imbalance.

See Next: Cognitive–Deliberate Practice

Back To: Industrial Behaviorism