As Your Resource For Self-Development

- The Optima Bowling Coach (2025)

Industrial Behaviorism

(Page Update 2/2/26)

Inside the Optima Bowling World, Industrial Behaviorism marks the historical moment when human performance was reconceived as measurable output. Development came to be understood less as a lived, unfolding process and more as a sequence of observable actions that could be isolated, timed, and optimized. Coaching evolved accordingly, shifting from tacit transmission and embodied judgment toward external measurement, standardized protocols, and quantitative benchmarks.

This epoch reflects what human development looks like when control is exercised primarily through metrics, and when improvement is defined by efficiency, consistency, and repeatability.

Historical Setting

The Industrial Revolution reshaped nearly every domain of human activity. Steam power, interchangeable parts, and expanding rail networks demanded uniform processes that could be replicated across dispersed sites. In this context, Frederick Winslow Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management formalized a new logic of work: analyze every motion, identify a single optimal method, and reward adherence to that method.

Educational systems followed the same template. Horace Mann’s common-school reforms introduced age-graded classrooms, standardized textbooks, and bell schedules that mirrored factory rhythms. In sport and physical training, early biomechanics laboratories employed high-speed cameras and stopwatches to dissect movement into analyzable segments. Across domains, efficiency became the organizing value: faster cycles, reduced variance, and predictable output.

The human being was increasingly treated as a mechanism to be tuned, rather than as a system developing across multiple planes of perception.

Coaching Expression

Industrial Behaviorism expressed itself through four dominant coaching practices, many of which remain influential today.

- Task Decomposition: Complex skills were divided into discrete sub-steps. Factory workers tightened a single bolt; bowlers isolated footwork, swing plane, and release into separate drills. Mastery was assumed to emerge from assembling perfected parts.

- Stopwatches, clipboards, and later video analysis quantified each component: Deviations from the prescribed pattern triggered immediate correction. Graphs and charts replaced the master’s glance as the primary evaluative tool.

- Manuals specified exact positions, angles, and sequences. Variation implied inefficiency; uniformity signaled competence. Coaching authority resided in adherence to protocol rather than contextual judgment.

- Piece-rate pay, grades, merit badges, and win-loss records reinforced compliance. Motivation was assumed to be driven by reward structures rather than intrinsic engagement. Together, these practices produced rapid gains in consistency and scalability—but at the cost of reduced adaptability when conditions changed.

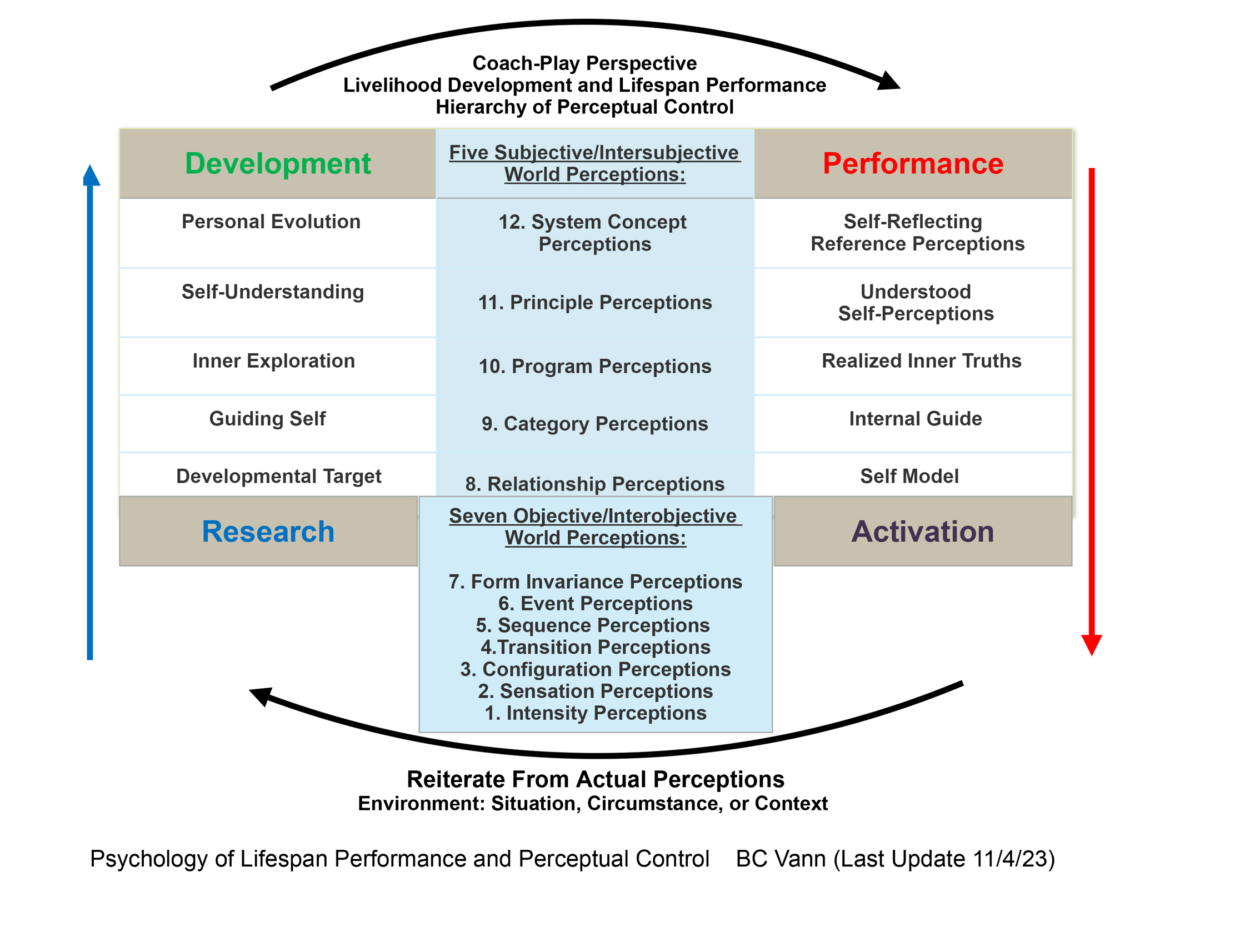

Development as Nested Perceptual Control

From a Perceptual Control Theory perspective, Industrial Behaviorism shifted control from the individual to the environment. Organizations regulated performance by imposing external reference values—production quotas, test scores, completion times—while leaving higher-order purpose implicit or unexamined.

LPPC analysis reveals that control was concentrated at the material–sensory plane. Sensory feedback loops were tightened through instrumentation, while relational–emotional signals were managed primarily to prevent fatigue or dissent. Symbolic–causal meaning was narrowed to narratives of productivity, progress, and national advancement.

When external metrics aligned with lived purpose, performance stabilized; When they diverged, motivation and coherence degraded.

Plane Balance

- Material–Sensory Plane: Highly amplified. Precision, timing, and mechanical consistency became the dominant indicators of development.

- Relational–Emotional Plane: Secondary. Emotional factors were acknowledged mainly as variables affecting output: fatigue, morale, and compliance.

- Symbolic–Causal Plane: Constrained. Purpose was abstracted into productivity goals, institutional success, and competitive outcomes, with little room for individual meaning-making.

This imbalance allowed large-scale coordination but limited self-regulation once external controls were removed.

PIE Integration Note

Within the PIE framework, Industrial Behaviorism emphasized Integrity and Experience as defined by measurement accuracy and protocol adherence.

Purpose shifted from lineage or vocation toward output targets: units per hour, test scores, win–loss records.

Experience condensed into numeric feedback, accelerating short-term improvement while risking long-term fragility when rewards diminished or metrics lost relevance.

Carry-Forward Legacy

Industrial Behaviorism left an enduring imprint:

- Objective measurement remains indispensable. Modern sport still tracks swing speed, launch angle, and split times.

- Instructional design inherits task decomposition. Learning objectives and backward mapping descend directly from this era.

- Efficiency thinking persists. Organizations continue to value scalability and predictability.

Its unresolved limitation lies in over-reliance on external control. When metrics replace meaning, curiosity, creativity, and self-regulation compress, setting the stage for later humanistic and cognitive revolts.

Reflection Prompt

List three performance metrics you currently track. For each, note one way it strengthens integrity and one way it might constrain purpose or relational depth. This contrast clarifies where measurement supports development, and where it may inhibit it.

See Next: Humanistic Revolt

Back To: Embodied Apprenticeship