As Your Resource For Self-Development

- The Optima Bowling Coach (2025)

Embodied Apprenticeship

(Page Update 5/18/25)

Embodied Apprenticeship designates the period in which learning was organized through face-to-face imitation and prolonged sensory immersion. Though largely implicit, developmental theory assumed that refined perception and disciplined repetition would coax latent capability into reliable action. Coaching, broadly understood, meant a master transmitting tacit knowledge to a novice through shared environments and sustained oversight.

Historical Setting

Until the mid-nineteenth century, most skilled activity unfolded inside small, craft-oriented communities—guild workshops, monastic scriptoria, musical ateliers, and martial arts schools. Written manuals existed, but daily progress depended on proximity to an exemplar whose embodied performance demonstrated standards unavailable in text. The economic structure reinforced this arrangement. Guild charters limited membership, protecting quality and preventing premature independence. A novice pledged years of service in exchange for lodging, materials, and the opportunity to observe techniques otherwise hidden from public view.

Outside Europe, parallel models prevailed. In Japanese dōjō culture, kata sequences choreographed proper stance, breath, and timing; in Chinese opera schools, children repeated stylized gestures until muscle fiber encoded the aesthetic code; in West African drumming lineages, polyrhythms passed ear-to-ear long before notation. Across regions, the organizing premise remained identical: the body was the primary storage device for skill, and correct shaping of that body required localized guardianship.

Technological constraints reinforced the pedagogy. Before mass printing, high-speed transport, and synthetic lighting, information moved at the speed of conversation, and practice sessions ended with sunset. Mastery had to be slowly layered into motor and sensory systems—what later theorists would call perceptual calibration and neural myelination—by repeating patterns inside stable physical settings.

Coaching Expression

The master-apprentice dyad governed daily routines. Instruction followed three recurring phases:

- Demonstration: The master executed a task—laying gold leaf, drawing a bowstring, carving a joint—at normal speed. The apprentice observed without interruption, absorbing kinaesthetic timing, grip pressure, and tool orientation. The speech was minimal; the body served as primary evidence.

- Guided Participation: The apprentice repeated the motion under close surveillance. Corrections arrived as brief directives (“closer to the grain,” “breathe before you pivot”) or as hands-on adjustments of limb position. Early iterations prioritized shape over the outcome; a flawed product could be remade, but a flawed habit would replicate indefinitely.

- Incremental Autonomy: Once reliability met the master’s threshold, the apprentice performed tasks unsupervised yet still inside the workshop’s acoustic and visual field. Periodic assessment safeguarded standards and provided progressive challenges—finer chisels, more complex melodic variations, and tighter blade tolerances.

The feedback cadence was continuous but local. The master’s glance, a raised eyebrow, or the silent removal of a defective piece delivered instant performance data. Written scores, numeric ratings, or formal examinations were rare. Success equaled the master’s nod and the community’s acceptance of finished goods.

Reward structures mirrored developmental milestones. Early tasks were menial—sweeping floors and mixing pigments. Though low status, these activities embedded novices in the workshop’s sensorial ambiance: resin scents, tool harmonics, and rhythm of mallet strikes. Such saturation helped the nervous system acquire craft-specific temporal patterns before fine motor refinements commenced.

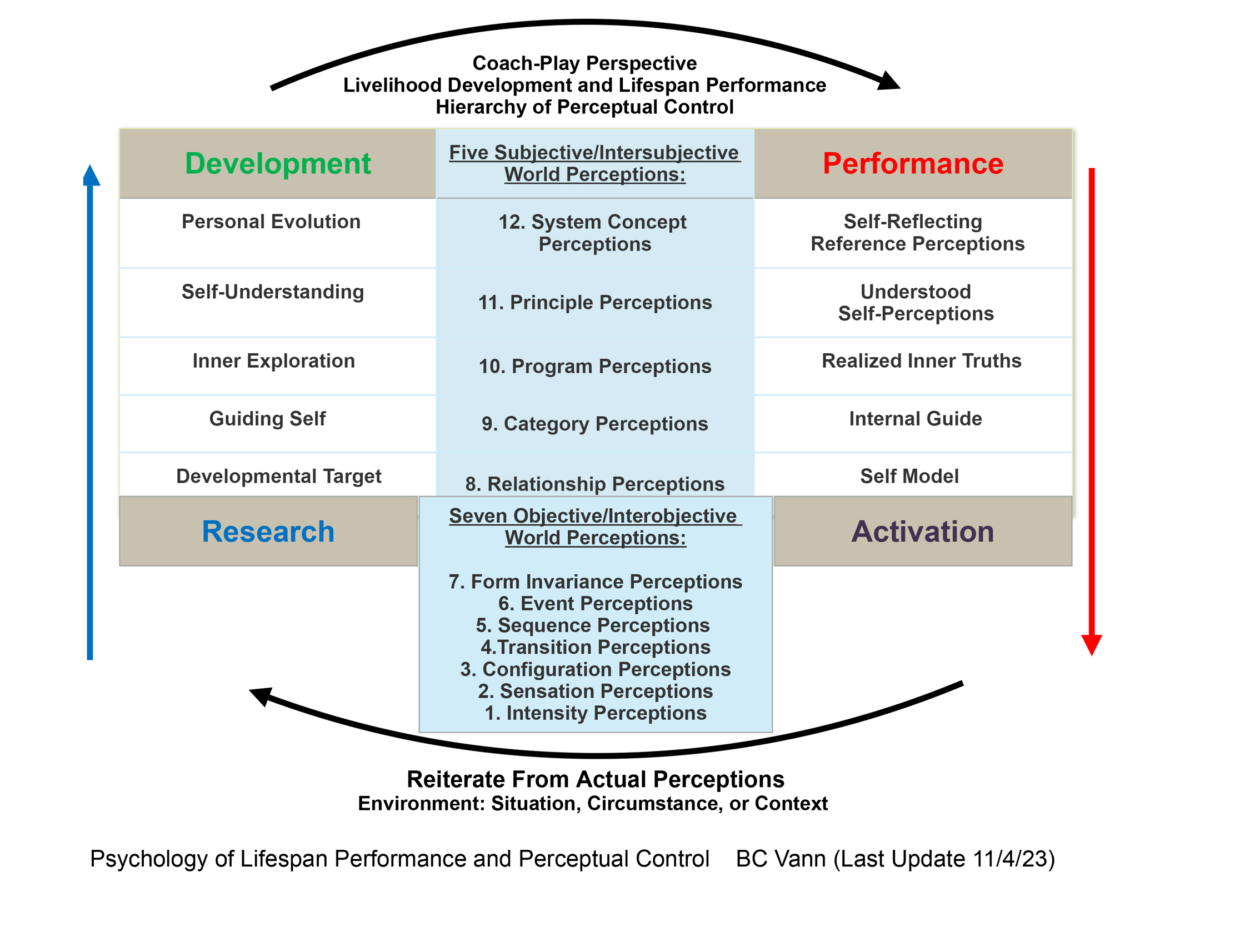

Development as Nested Perceptual Control

Embodied Apprenticeship — PCT Lens: Masters controlled apprentices’ sensory alignment by adjusting task difficulty and workspace rhythm; reference values came from craft lineage.

Plane Balance

Material-Sensory considerations dominated. The apprenticeship sought precise tension between muscle, tool, and substrate. Visual, tactile, and auditory cues determined correctness; relational signals remained background.

Relational-Emotional dynamics surfaced mainly as respect hierarchies—obedience to the master solidarity among peers; emotional regulation aimed at humility and endurance rather than personal exploration.

Symbolic-Causal framing resided in the lineage story: the guild’s crest, the monastery’s rule, and the warrior code. These narratives justified the labor but rarely underwent explicit debate. As a result, meaning remained stable but under-examined; intellectual re-interpretation was unnecessary so long as products met communal expectations.

PIE Integration Note

Purpose was inherited rather than negotiated. The apprentice’s objective aligned with the workshop’s reputation and the master’s honor. Integrity is derived from unbroken sensory feedback loops, such as direct perception of wood grain, steel temper, or vocal resonance. Because the entire learning cycle stayed inside one spatial arena, feedback latency was minimal and corruption risk low. Experience accumulated through thousands of micro-iterations, each contributing subtle calibration. The triad’s balance favored Integrity and Experience; Purpose, treated as self-evident, received the least elaboration.

Carry-Forward Legacy

Features of Embodied Apprenticeship that endure:

- Deliberate Repetition within Constrained Variability: Modern batting cages, ballet barres, and flight simulators replicate the tight parameter windows of medieval forges, proving that early crafts understood the learning value of controlled environments.

- Sensory Modelling before Verbal Explanation: Video analysis in sports coaching still begins with “watch this clip,” mirroring the master’s first silent demonstration.

- Status-Graded Responsibility: Medical residencies echo the scaffold: observe, assist, operate under supervision, and operate independently.

Unresolved tensions also persist. Apprenticeship’s success at embodied precision came at the cost of personal agency and theoretical flexibility. When external shocks—new materials, changing markets—arrived, closed workshops struggled to adapt, revealing the limitations of lineage-centric purpose.

Reflection Prompt

Identify one skill you currently practice. Remove all analytic commentary—metrics, verbal cues, conceptual labels—and attend only to sensory signals for a single session. Afterward, note whether heightened perception altered execution quality. This exercise replicates the apprenticeship reliance on unmediated feedback and clarifies how modern tools may either enhance or distract from such fidelity.

Cross-Links

- See Industrial Behaviourism to examine how external measurement replaced the master’s intuition.

- Consult Performance Authentication for methods that reintegrate sensory fidelity within contemporary feedback systems.

See Next: Industrial Behaviorism