As Your Resource For Self-Development

- The Optima Bowling Coach (2025)

The First Step: Learning How to Think

(Page Update 1/11/26)

Bowling coach and BowlU founder, Rick Benoit, made this interesting point on Facebook today (11/10/25): “Most of the time, how to think is more important than what to think.” That line is expanded here because it is foundational. It identifies the turning point in human development. In that moment, thinking becomes a function we can consciously utilize to govern self-control. Instead of a stream, we merely ride.

When people are trained only in what to think, their minds borrow conclusions from their feelings, groups, or idols; when they learn how to think, perception stabilizes, and chaos begins to sort itself into patterns. Unfortunately, too many people are overfocused on what to think, and not enough of us want to learn how to think. How to think is the key sensible ability, and the first step to conscious performance. Only by learning how to think can one begin to work on resolving the primary wicked problem, humanity's misunderstanding of what the hell is wrong with this crazy, emotionally imagined, and idiotic world of ours.

In developmental terms, this is the threshold at which the emotional dimension ceases to dictate, and the mental dimension begins to govern one’s conscious performance. How to think is not a style preference; it is a control function that allows consciousness to examine its own contents, to observe, differentiate, relate, as a dependable, self-activated, integrated intelligence. It is the first discipline of a controlled life and the opening level of the Four Steps of Conscious Performance.

Any confusion and craziness in this world of ours is largely connected to undeveloped human potential. Emotion imagines; mind clarifies. But when emotion runs the show, imagination hardens into a pontificated doctrine of what to think that proliferates into warring certainties. When a fully integrated mentality assumes its proper function, emotional imagination is liberated to serve by supplying images and passionate energy, which thinking then governs consciously to approach actuality. This re-ordering is not abstract; it is practical. It turns friction into feedback and noise into information.

Below, I will share the process for negating craziness. Let's continue in that vein to discover what I mean by "Human development is the flow through research, development, performance, and activation."

Intelligence, Development,

and the Quiet Discipline of Conscious Performance

For much of human history, thinking itself was not a subject of inquiry. People learned skills, customs, stories, and practices that allowed them to survive, cooperate, and make sense of the world they inherited. Intelligence, such as it was understood, expressed itself through competence within those shared forms. There was little need to step outside one’s thoughts to examine how it worked, because the environments in which human life unfolded were comparatively stable and slow to change.

That condition no longer holds. The modern world confronts human beings with levels of complexity, speed, and abstraction that far exceed those encountered in earlier times. We are required to coordinate multiple perspectives, navigate large-scale systems, regulate emotional pressure, and make decisions whose consequences may unfold and influence over long time frames. Under these conditions, it is no longer sufficient to know what to think. What increasingly determines coherence or confusion is how one's intelligence operates. Learning how to think has therefore become a developmental necessity.

Intelligence as Levels of Thinking

One of the central misunderstandings of modern culture is the treatment of intelligence as a single faculty or a fixed trait. In reality, intelligence expresses itself through distinct levels, or forms of thinking, each capable of resolving different kinds of problems. At the mental level, intelligence manifests through four primary forms of thinking:

- Discursive-Inference Thinking: Which operates sequentially through inference, repetition, and comparison.

- Principle Thinking: Which abstracts governing relationships and rules from experience.

- Perspective Thinking: Which integrates multiple viewpoints and contexts.

- Systems thinking: Which perceives wholeness, feedback loops, and long-term dynamics.

These are not stages one outgrows. They are enduring sensible abilities. Once developed, they remain available for use as circumstances require. Mature intelligence does not abandon discursive thinking; it employs it when precision and effort are needed. It applies principles when structure is required; It does not discard them. It does not relinquish perspective or systems awareness; it uses them when complexity demands integration. What changes with development is not the existence of these levels, but where consciousness is centered (self-activated), and then, how naturally the appropriate form of thinking is employed.

Beyond the mental levels lies causal-intuitive intelligence, sometimes described as the world of ideas. This is not a more complex form of mental reasoning, nor an extension of systems thinking. It is a different mode of intelligence altogether: one in which ideas are apprehended directly rather than inferred. Mental thinking becomes an instrument at this level, not the source of understanding. Learning how to think involves becoming conscious of these distinctions, not in a technical sense, but as a lived reality.

The Dimensions of Being Human

Human intelligence does not operate in isolation from the rest of human experience. It is expressed through and constrained by the three dimensions of being human:

- Physical-Etheric: Which governs habit, repetition, and the rhythms of bodily life.

- Emotional (Repulsive-Attractive): Which governs valuation, attachment, aversion, and motivational force.

- Mental-Causal: Which governs meaning, understanding, and the intelligent use of thought.

A higher dimension of being human, provided that consciousness has centered within that particular dimension, can govern the next-lower dimension. When consciousness is centered in the emotional dimension, the physical body is regulated through attraction and repulsion (i.e., care, desire, avoidance, effort, hate, and love). When consciousness is centered in the mental dimension, emotion becomes governable through the sensible ability of thinking, not suppression, but as self-control.

Importantly, this governance is developmental. Thus, rather than momentary, once consciousness has stabilized at a given level, it does not lose its sensible ability. Development does not require constant effort to “stay centered.” Instead, intelligence becomes naturally available in the forms required by the situation. This is a crucial point: Conscious performance is not vigilance; it is maturity.

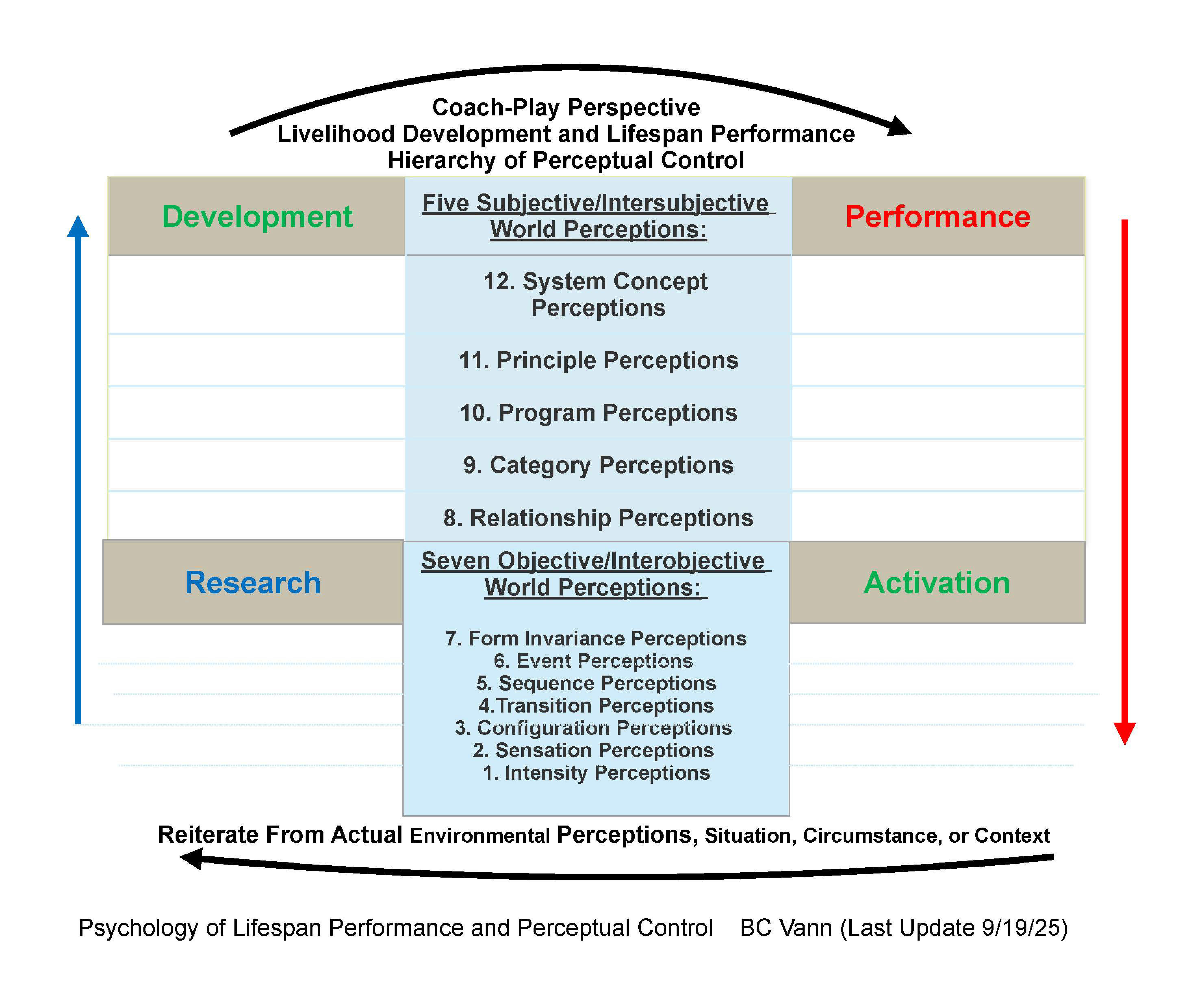

Development Through LPPC

The mechanism by which intelligence becomes stable is not willpower or discipline alone. It is human development, as described by the LPPC model: Research, Development, Performance, and Activation. In research, intelligence explores and questions reality. In development, understanding is integrated into sensible abilities. In performance, ability is expressed in lived action. In activation, consciousness stabilizes at the newly developed level. Once activation has occurred, what has been gained is not lost.

This cycle operates continuously across a lifespan. Performance to Activate and Livelihood Development explains why genuine development appears irreversible, even though its expressions can vary across contexts. A person, under pressure. Those who have developed perspective thinking do not lose it; they may temporarily rely on simpler forms of thinking, but the higher sensible abilities remain available and return naturally when situations dictate. Learning how to think is inseparable from the activations of one's development. It is not something one does once, nor something one maintains through constant self-monitoring. It is something one becomes through lived integration.

The Limits of Unexamined Thinking

Much of what passes for thinking in daily life is reactive (stimulus-response). Thoughts arise automatically in response to emotional cues, social pressures, and habitual interpretations. This is not a failure of intelligence; it is intelligence operating at a level that has not yet been brought into conscious relationship with itself. When thinking remains unexamined, mechanical and unintentional, several predictable patterns emerge. Emotion drives interpretation. Identity becomes fused with opinion. Disagreement is perceived as a threat rather than as information. Decisions are made quickly but often without coherence across time.

At a personal level, this manifests as recurring conflicts, poor decisions under pressure, and a sense of being driven by forces one does not fully understand. At a collective level, it manifests as polarization, institutional rigidity, and the persistence of problems that no amount of information seems to resolve. The issue is not ignorance. It is a misalignment between the level of thinking employed and the complexity of the task.

Learning How to Think as a Responsibility

Learning how to think means taking responsibility for the inner conditions (level of development) that shape outer life. This responsibility is not moralistic or self-critical. It is architectural. It recognizes that clarity, coherence, and integrity are refined from within rather than imposed from outside. This does not mean becoming endlessly self-analytical. In fact, excessive introspection often signals that intelligence has not yet stabilized at a level capable of integrating experience efficiently. Mature thinking simplifies rather than complicates. It allows decisions to be made with steadiness, even in the presence of uncertainty. Responsibility, in this sense, means recognizing that intelligence must now be used consciously. Not forced, not strained, but applied appropriately.

Causal-Intuitive Intelligence and Meaning

At the causal-intuitive level, intelligence no longer works primarily through comparison or inference. Ideas are apprehended directly. Meaning precedes formulation. Mental thinking is employed deliberately, not compulsively. This level does not replace mental intelligence; it governs it. Discursive-inference thinking, principle thinking, perspective thinking, and systems thinking remain fully available but are organized around insight rather than reaction.

From this level, coherence is not something one strives to maintain. It arises naturally from a fully integrated intellect at the highest level of being human. Integrity ceases to be an ethical aspiration and becomes structural alignment between intention, perception, and action. This is why causal–intuitive intelligence cannot be taught in the conventional sense. It emerges when mental intelligence has been sufficiently developed and integrated. Learning how to think prepares the ground for this emergence but does not force it.

Conscious Performance as Natural Expression

Conscious performance is often misunderstood as effortful control, keeping oneself centered, regulating reactions, and managing inner states. But, actually, conscious performance is the natural expression of one’s developed intelligence. When intelligence has matured, the appropriate form of thinking is employed without strain. Lower levels remain available and useful; higher levels govern without effort. The individual does not “manage” their thinking; they use it. This is why conscious performance feels calm rather than intense. It conserves energy. It reduces inner conflict. It allows action to arise from understanding rather than compulsion.

Why This Matters Now

The requirement for conscious performance is not a moral judgment on humanity. It is a structural consequence of the world humanity has created. The systems we now inhabit demand levels of thinking that must be consciously available if coherence is to be maintained.

Learning how to think is, therefore, not an abstract philosophical exercise. It is a practical response to a developmental threshold. It invites intelligence to become what it already has the innate capacity to become. This invitation is quiet, but decisive. It does not ask for perfection. It asks for consciousness (awareness, spirit). It asks for responsibility. And it asks for patience with a process that unfolds across a lifetime. Learning how to think is not about thinking more. It is about thinking from the right level, at the right time, for the right reason. That is the foundation of conscious performance.

Return To: Four Steps of Conscious Performance